Silence Is Not An Option

If a tree falls in the woods and no one ever hears it fall, does it make a sound?

Well, according to metaphysicists, no it does not.

In the metaphysical sense, sound can only occur if there is conscious hearing, Without the presence of an audience, sound does not exist.

But can the same be said of social media? If we scroll through some posts and never leave a comment, have we truly been silent?

Nope.

When it comes to the internet, there's no such thing as true silence because every action you take, no matter how small, is in front of an audience - even if you are not aware of their presence.

Earlier this month I was invited as a guest on Deutschlandfunk, German National Radio (like the BBC, but in German) as a global expert on internet lurking to discuss how silence operates online.

If you happen to speak German (or want to hear what I sound like in German voice, over you can click yellow face the link below.

The host was kind enough to have the audio transcript translated into English for me and you can read the podcast text below.

Social Media – Why so many people are silent online

Author: Luca Rehse-Knauf

Editorial team: Kathrin Kühn

Length: 19′

Broadcast date: 10 Jul 25

Production date: 09 Jul 2025

Interview partners:Gina Sipley, media scholar at the State University of New York, author of Just Here For The Comments: Lurking As Digital Literacy Practice (https://www.ginasipley.com/) Stephan Schölzel, media educator in open youth work (https://www.linkedin.com/in/stschoelzel/?originalSubdomain=de)Philipp Lorenz-Spreen, network scientist at the Technical University of Dresden, researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development (https://www.mpib-berlin.mpg.de/mitarbeiter/philipp-lorenz-spreen)

Kathrin Kühn: Today’s episode is about this … (pause) – the silence … of so many people on the net, on social media – and the consequences that has. Twenty minutes – by Luca Rehse-Knauf and Lea Marie Meier.

OT1 Gina Sipley:“Reading, the hovering, the clicking on links, enlarging an image, scrolling, tapping on your phone. The platform can see everything that you're doing.”

Lea Marie Meier: The digital realm has its own rules. And it is used very unevenly.

OT2 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen: “If it is mainly extremely outspoken or particularly active political voices who express themselves, and they do so disproportionately, then we do not have a representative discourse – yet it is sometimes interpreted and perceived as one.”

OT3 Stephan Schölzel: “This clearly shows how low the threshold can be for feeling afraid to express oneself publicly.”

Lea Marie Meier: Lurking: Why so many stay silent online.

Music

Lea Marie Meier: The Internet arrived with a great promise.

OT4 Telekom: “The data highway – it will connect us all.”

Lea Marie Meier: So proclaimed a 1995 Telekom commercial. The message: easy participation, everyone can speak publicly. But it quickly became clear – only a few actually do.

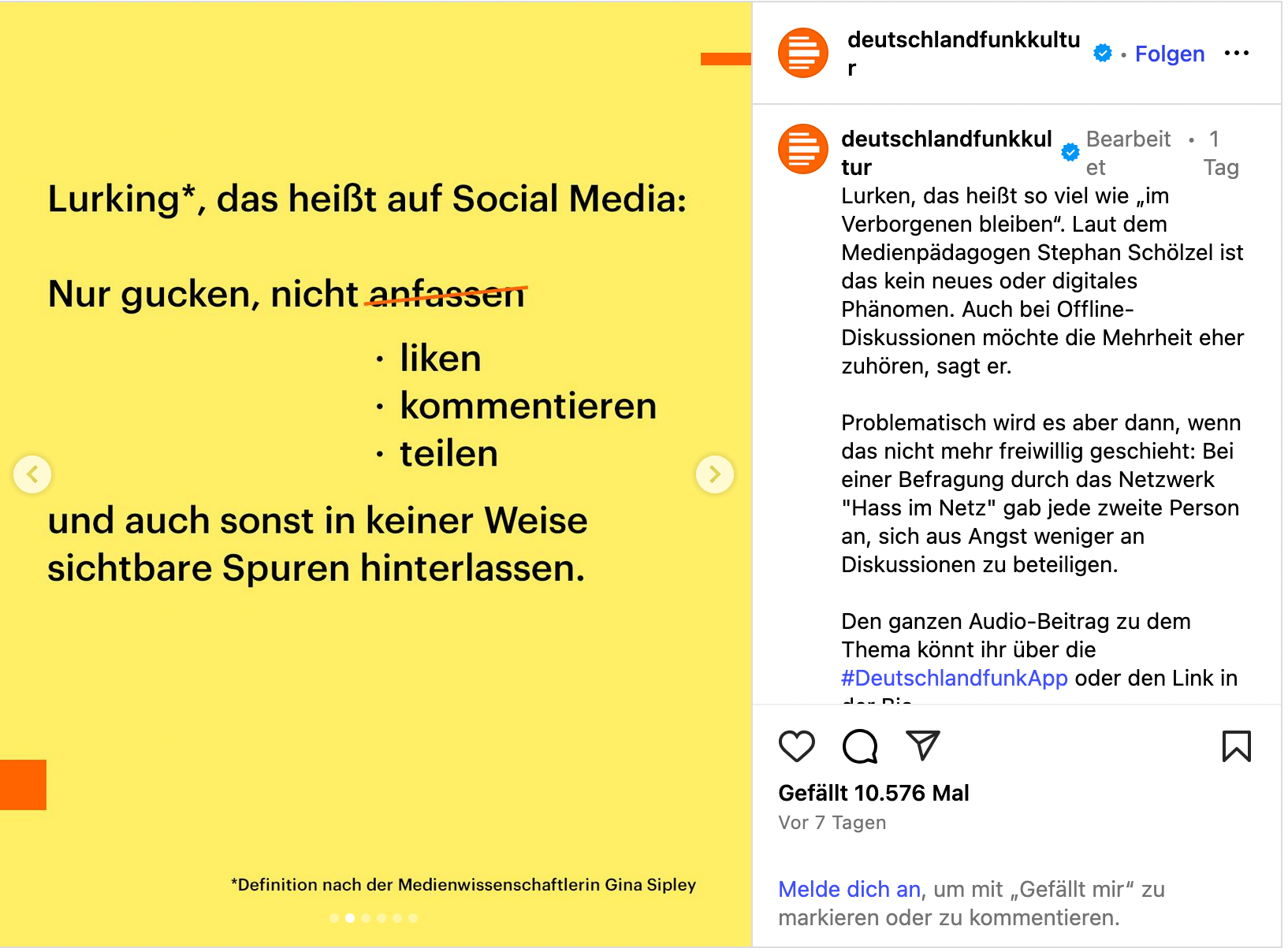

OT5 Gina Sipley:“There are lots of different ways to define lurking. The way that I use, it's when you are on social media and you are reading content, but you're not liking, commenting, sharing, or leaving a visible trace of your participation to your peers.”

Lea Marie Meier: Gina Sipley is a media scholar at the State University of New York. She studies the phenomenon of lurking – digital silence. We have had numbers on it for quite some time. Around the year 2000, internal website studies and academic estimates concluded: depending on the community and platform, up to 90 percent of online activity consists of silent reading. A finding that has almost become a cliché: the majority remains silent.

Music

Lea Marie Meier: Online silence has existed since the first digital communities. In 1983, New York Times journalist Robert Lindsey first described the phenomenon of quietly being present. People exchanged ideas via early networks such as CompuServe – text-based, in groups, about everything: agriculture, nuclear power, erotica. Some wrote. Others only read. Lurking had something disreputable about it.

OT6 Gina Sipley: “There was a brief period in the late 1990s, early 2000s, where lurking was being described as folks who are selfish free riders, people who are taking from the group but not contributing.”

Lea Marie Meier: But even that verdict soon wavered. In the early 2000s, Canadian information scientist Blair Nonnecke showed in a comprehensive study that people stay quiet online for many different reasons: reading is enough for them, they are shy, have no time, or do not want to further overload chaotic discussions.

Short music sting

Lea Marie Meier: Online silence is therefore complex. And researching it is not easy. When you look at social networks, you see comments, likes, shared content – but that is only the tip of the iceberg. Much of what happens on platforms takes place hidden from view. Research therefore distinguishes between public metrics and hidden micro-metrics, silent participation.

OT7 Gina Sipley:“The private participation is going to be the reading, the hovering, the clicking on links, enlarging an image, scrolling, tapping on your phone. And then remember, they're private to your peers, but they are not private to the platform. The platform can see everything that you're doing. The challenge, though, is when you consider that 90% of participation is lurking – if you are only scraping the publicly facing metrics, you're only getting 10% of the given population you're trying to study. And that could potentially lead to flawed results.”

Lea Marie Meier: Completely withdrawing is thus impossible online. And to truly understand the dynamics of social networks – digital behavior – it is important to reach the silent. For a 2024 study, Gina Sipley surveyed silent members of fifteen Facebook groups with more than 100,000 members in total. Her question: why don’t they write?

Music sting

Lea Marie Meier: One finding: many who read online want to understand. Many respondents also knew very well how powerful small online interactions can be.

OT8 Gina Sipley: “Many of the folks I interviewed said they would purposefully not comment, not like, not share. They might talk about the post with other people in real life, or on text message, or on another platform — but they don’t want that particular post to spread and the best way to contain it is, to not give it attention.“

Lea Marie Meier: In fact, several participants in the study chose to ignore posts they considered politically dangerous, so as not to feed the algorithm. Conscious silence – for Gina Sipley that, too, is a form of media literacy.

OT9 Gina Sipley: “But I would also argue that resisting the urge to continually reread it and revisit it will also help to contain it. What you read becomes what other people see. So if you spend a disproportionate amount of time reading things that are troublesome, they will wind up in other people's feeds.”

Music sting

Lea Marie Meier: What appears in the feed quickly ends up in the analogue world. Those who like or comment online can feel offline consequences.

Quote 2: “I always thought: if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear … But nowadays you have to be careful what you post. People take screenshots of what you write.”

Lea Marie Meier: one participant tells Sipley. Another was confronted at work with a post in which she cheered about a snow day that had kept her at home.

Quote 3: “I see no problem in posting: ‘Yay, a snow day!’ Everyone likes snow days … but apparently some think that looks unprofessional, as if you don’t like to work. How others interpret your words becomes your problem. And I don’t need more problems.”

Lea Marie Meier: Nothing online is fleeting; every seemingly minor comment is recorded by the platform.

OT10 Gina Sipley: “So there a sentiment among people that it better to only post when it absolutely necessary. That's one small example but people are aware that what they put out publicly could come back to haunt them later so there's a resistance sometimes to posting for that reason.”

Lea Marie Meier: Gina Sipley published her study as a book: Just Here for the Comments. On the cover: a bucket of popcorn – symbolising a key motivation behind lurking. One participant described lurking as “mindless entertainment”; like sitting comfortably in a dark cinema – simply watching.

Quote 4: “It’s funny, but you’re almost tense, because you know someone is going to be really mean to someone else. And it’s funny, but it makes you nervous. It’s really not good. It’s addictive, but it’s not good for you.”

Lea Marie Meier: Reading comments as a guilty pleasure, a secret indulgence. Another said it was like watching a car crash.

Quote 5: “You see people arguing, trying to stay calm and collected. And then someone comes along and just completely beats them up in the comments, and I only think: ‘That is totally unnecessary.’”

Lea Marie Meier: Online discussions can therefore be thrilling – but they can also be literally off-putting.

Music

Lea Marie Meier: Withdrawing online, observing, reading instead of speaking – that is not a problem per se. Participation is an option, not an obligation.

OT11 Stephan Schölzel: “I think the pre-digital analogue form of lurking were the people who sat and listened while the philosophers, poets and thinkers spoke on stage. The majority then didn’t go up afterwards for big discussions; they went home, ate something, went to bed – end of day. Most people prefer to listen; not everyone wants to take part in every discussion. That is quite normal.”

Lea Marie Meier: Stephan Schölzel is a media educator and coordinates the Hessen branch of the Society for Media Education and Communication Culture. He offers media-literacy training and knows from practice why people stay silent online. He says: the reasons matter. Is it also fear? Because: those who watch others being attacked consider twice before speaking themselves. The Competence Network Against Online Hate surveyed people about exactly this. The result: one in two said they participate less in discussions due to fear. Nearly 90 percent felt that hate speech has increased in recent years.

OT12 Stephan Schölzel: “Of course, in everyday work you notice people who have already experienced something and no longer want to speak up.”

Lea Marie Meier: Schölzel works with teenagers in Neu-Isenburg, Hesse, and knows well how a small Instagram comment can trigger a harsh reaction. The pictures you post can become weapons.

OT13 Stephan Schölzel: “It can just be a pupil who said, ‘Hey, I don’t find your town very pretty.’ That was the spark. Then someone from that place felt personally attacked and said, ‘You and your horse stable – I found on Instagram where you go to school, that you work at a stable – horses are crap, didn’t you know?’ That actually happened. And it was enough for someone to scroll through the entire Insta timeline, digging out everything. It read a bit like a threat: I know where you live, who your friends are. That can happen, and when it’s suddenly about serious topics, the fear grows exponentially.”

Lea Marie Meier: Certain groups are especially targeted by online hate: people with visible migration backgrounds, queer people and young women. Outside protected digital spaces, almost everywhere.

OT14 Stephan Schölzel: “Another example, especially from gaming: female players who do not speak in voice chat, choose clearly male usernames, and try not to reveal they are women – because they know it will have negative consequences, even in voice chat alone. That is simply depressing, and it shows how low the threshold can be for fearing to speak publicly if being perceived as female is already enough.”

Lea Marie Meier: All of this has consequences. Digital public space is used asymmetrically. More men speak, fewer women. In the worst case, people withdraw completely from political discourse – on big issues and on small local matters where every voice counts.

OT15 Stephan Schölzel: “Take a debate about introducing a bike street in a town: the municipal account posts, people comment, and worlds collide – from traffic-planning ideas to language like ‘Go back to your country’ because someone in a photo wears a headscarf. If citizens no longer want to take part in discourse, even on supposedly protected platforms that cannot truly be safe because they aren’t German platforms – something starts to go wrong.”

Lea Marie Meier: Wanting to say something but not daring can be burdensome, emotionally as well. It can dent self-esteem. Another consequence: discourse risks becoming polarised. Few, often extreme, voices are over-represented. So says Philipp Lorenz-Spreen, network scientist at TU Dresden, who researches digitalisation and society.

OT16 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen: “If you speak of public debate but really mean what a few people say on Twitter, you produce a distorted discussion that is supposed to reflect public discourse, but perhaps does not.”

Lea Marie Meier: Especially when the democratic ideal is that discussions reflect society’s perspectives as broadly as possible.

OT17 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen: “A minority opinion that may be more extreme than the mainstream suddenly becomes something real when it is reported in the news, when topics repeatedly discussed on social media appear in other media too. Eventually you have that distorted debate everywhere – and it becomes part of our society.”

Music

Lea Marie Meier: Platforms reward what polarises: provocation, conflict, outrage. Content and voices that encourage quiet reflection struggle – or fall silent. Yet it could be different. Lorenz-Spreen is part of the Prosocial Design Network, gathering knowledge on alternative platform designs.

OT18 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen: “One possibility would be to rethink the reward mechanisms for positive social feedback, for example.”

Lea Marie Meier: One example: a thank-you button next to the like button – to say, I don’t agree, but I appreciate that this was raised. Affirmation and appreciation encourage participation, even online.

OT19 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen: “There are also studies that award badges for especially constructive comments – a kind of ‘constructive comment’ medal you can collect. Testing showed this can motivate people to write more constructive comments, which in turn could make others feel less put off by the discourse.”

Lea Marie Meier: In analogue spaces, like a town square, you can gauge who is talking, how many are watching. If a post online gets 200 likes, it may look popular. But if 10,000 people saw it and did not react, that puts it in perspective. Platform operators could make participation more visible so users can better assess content.

OT20 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen (alternative): “Think of the marketplace: someone a bit eccentric shouts odd opinions; a few people stand by and nod, but most shake their heads and walk on. Offline we have learned to read social situations like that. Online metrics are hard to intuit, and we often lack information.”

Lea Marie Meier: In a recent field study on Reddit, Lorenz-Spreen and colleagues measured what actually stops people from commenting and what might encourage them. The result: one group – male, politically interested – feels spurred on by confrontational discussion. Others find a toxic tone repellent.

OT21 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen: “So the gap widens between those who participate and those who don’t. You could adjust that by better moderating content, moderating hate speech, so the discourse doesn’t become so toxic and those put off feel less so and join in again.”

Lea Marie Meier: Platform design has a huge impact on communication culture.

OT22 Philipp Lorenz-Spreen: “Reddit is quite interesting: first, it has different subreddits with very different cultures; overall, comment sections regulated by up- and downvotes and sorted accordingly, with comment trees, often seem – let’s say – more constructive than comments on other platforms that are sorted solely by likes and not in tree form, making argument chains harder to follow.”

Music sting

Lea Marie Meier: Platforms are spaces that we humans fill. Algorithms amplify only what we psychologically latch onto. Media educator Stephan Schölzel therefore calls for a kind of personal responsibility that applies online just as offline.

OT23 Stephan Schölzel: “There are differences between social interactions, but one is not less real than the other. Separating digital and analogue civil courage is not helpful. I’d say: civil courage – regardless of the space – is a very good goal.”

Lea Marie Meier: Meaning: if someone is attacked, say something, ask, lend support – provided you don’t endanger yourself. And for media scholar Gina Sipley, media education remains key: revealing hidden dynamics online.

OT24 Gina Sipley: “And I think that as we continue to evolve, particularly in the age of AI right now, folks need to understand how their participation, when to publicly participate and when to withhold their data and to understand that their reading and their attention is very valuable, and they can choose when to engage and when to withhold.”

Lea Marie Meier: Because truly staying silent online is impossible.

Music

Kathrin Kühn: That was Systemfragen about lurking – why so many stay silent online. By Luca Rehse-Knauf. I’m Kathrin Kühn, in charge of the editorial work. Voices you heard: mainly Lea Marie Meier, but also Oliver El-Fayoumy, Anja Jazeschann and Nina Lentföhr. We welcome feedback at systemfragen@deutschlandfunk.de. This episode was recorded on 9 July 2025.

I look forward to sharing more about Aurora Bookshop by Gina Sipley next month. Until then -

Thanks for walking beside me,

If you know someone who might be interested in receiving this newsletter, please forward and encourage them to subscribe.